Air pollution is an important and neglected cause of death in children in low-income countries

In 2015, around 4.5 million people died prematurely from diseases attributed to ambient air pollution, including 237,000 children under the age of five from respiratory infections. This is the result of a study published by the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry in Mainz and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), around one million children younger than five years died from lower respiratory infections in 2015. Fine particulates smaller than 2.5 microns in diameter (PM2.5) play a decisive role. Fine particulates penetrate deeply into the respiratory tract, and as a result can increase the risks of respiratory infections, ischaemic heart disease (heart attacks), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cerebrovascular disease (strokes) and lung cancer. Between 2000 and 2015 the global average concentration of fine particulate matter to which humans are exposed has increased from around 40 to 44.0 micrograms per cubic meter of air. This is more than four times the concentration of 10 micrograms recommended by the WHO as an upper limit for annual mean exposure. The irritant gas ozone also contributes to respiratory health effects.

The origin of particulate matter differs from country to country: in India, for example, the burning of solid fuels for cooking and heating is the most important single source, whereas power plants, transport and agriculture are the largest sources in the USA. The air inside buildings from household pollution can also pose a major health risk, but the focus of a study published in the journal The Lancet Planetary Health on 29 June 2018 is on ambient air.

122 million years of life were lost through early deaths

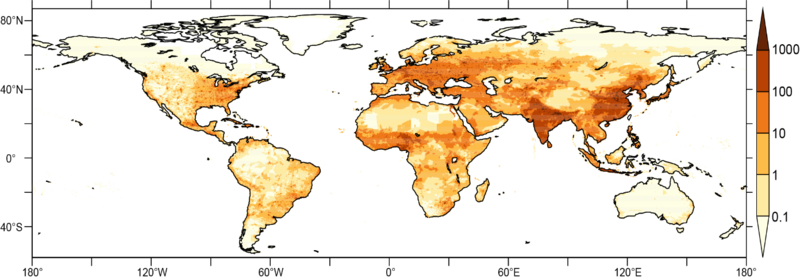

The researchers Jos Lelieveld, Andy Haines and Andrea Pozzer have determined the exposure to particulate matter and ozone with an established global model of atmospheric chemistry. They linked the ambient (outdoor) air pollutant concentrations to data on population as well as disease occurrence and causes of death in different countries. They calculated that in 2015 worldwide about 270,000 excess deaths occurred from exposure to ozone and 4.28 million from particulate matter. The causes of death included 727,000 people with lower respiratory tract infections, 1.09 million with COPD, 920,000 with cerebrovascular disease, 1.5 million with heart disease and 304,000 with lung cancer. As a result of these excess deaths, worldwide 122 million years of life were lost in 2015. These figures, the authors say, are lower limits because other diseases, which may also be related to air pollution, have not been taken into account.

Inadequate medical care and malnourishment increase the danger for children

The study focuses on children under the age of five who may be particularly sensitive to the effects of air pollution on respiratory infections. The calculations showed that in 2015, out of a total of 669 million children under five around the world, about 240,000 died from poor air quality as a result of lower respiratory tract infections, particularly pneumonia.

In comparison, 87,000 children died from HIV/AIDS, 525,000 from diarrhoea and 312,000 from malaria in the same year. The likelihood of children dying from polluted air was particularly high in Africa. In low-income countries, curable diseases often cause death because many children are undernourished and medical care is inadequate. In Chad for example, the health risk for children from ambient air pollution is almost ten times higher than the global average. Life expectancy is substantially reduced. In sub-Saharan Africa, children lose four to five years of life expectancy on average due to ambient air pollution.

'A three-pronged strategy is needed'

The study also shows that in some lower to middle income countries, notably India and Pakistan, the mortality rate for girls is 1.2 times higher than for boys, which may reflect differences in nutrition and health care. On the other hand, the study shows that in India child mortality due to air pollution is declining, probably because health care, household air pollution and nutrition are improving.

Nevertheless, as ambient air quality continues to deteriorate, the cause of mortality shifts to other diseases and older people. The authors call for a three-pronged strategy to prevent child deaths from air pollution: adequate nutrition combined with improved health care and air quality.