Ancient Teeth Reveal Mammalian Responses to Climate Change in Southeast Asia

New isotopic analysis of fossil teeth uncovers how dietary flexibility determined survival or extinction over the last 150.000 years

Press release of the Max Planck Institute for Geoanthopology, Jena

Understanding how species survive environmental upheavals is central to evolutionary and

conservation science. Southeast Asia, one of the world’s most biodiverse regions, has repeatedly

swung between forests and grasslands over the last 150.000 years. Until now, however, little was known

about how ancient mammals in these tropical landscapes adapted—or failed to adapt—to these

dramatic shifts.

A new study published in Science Advances and led by the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology uncovers how flexibility made the difference between survival and extinction. By analyzing fossil teeth from Vietnam and Laos, an international team reconstructed the diets and habitats of extinct, extirpated, and still-living species. The results show that animals with varied diets and habitats were more likely to endure, while narrow specialists largely disappeared.

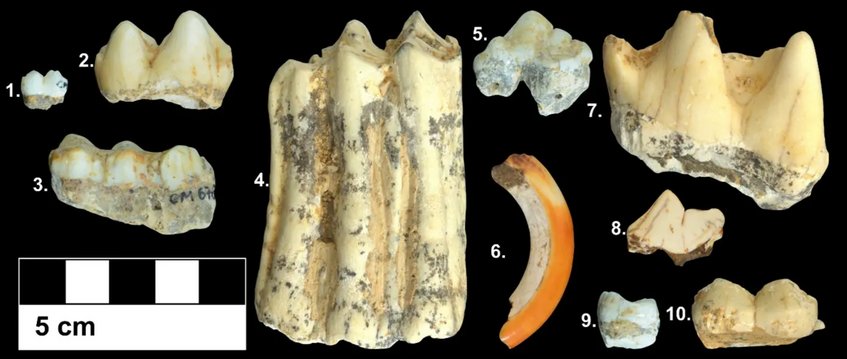

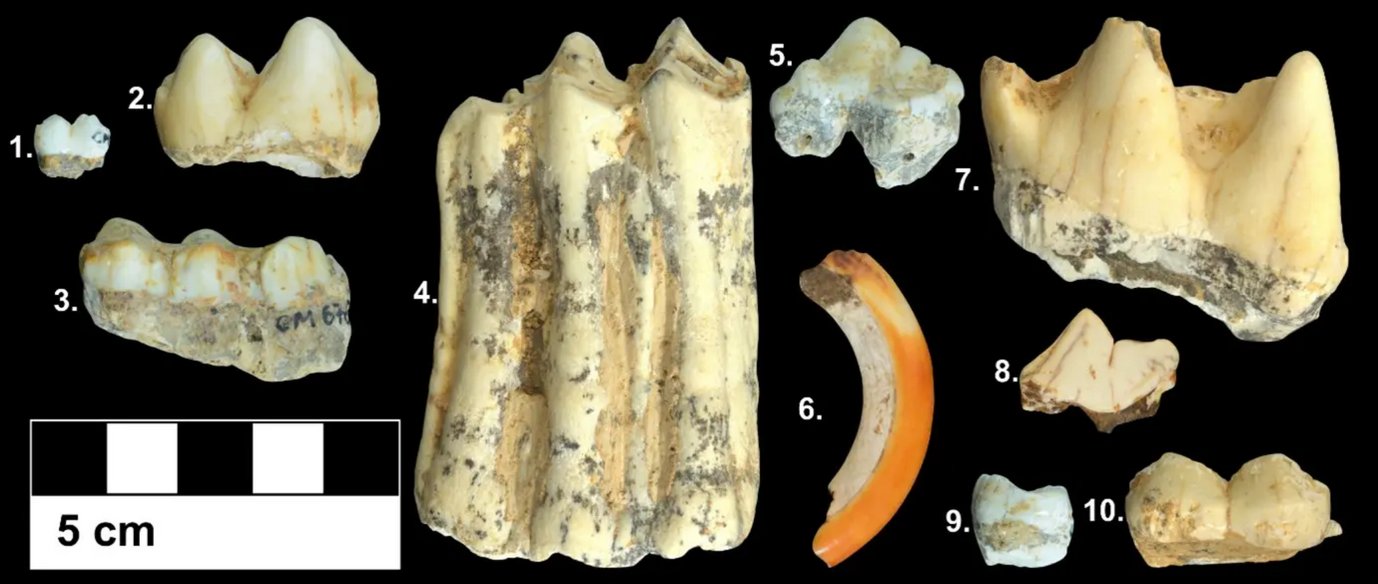

The team, which also included researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, examined 141 fossil teeth dating from 150,000 to 13,000 years ago and combined them with existing records. Using stable isotope analysis of carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, and zinc, they examined dietary responses to environmental shifts.

“By analyzing chemical traces in tooth enamel, we can piece together ancient diets and environments in remarkable detail,” says lead author Dr. Nicolas Bourgon. “Comparing species across time shows why some survived while others vanished.”

Animals like sambar deer, macaques, and wild boar proved adaptable, as reflected in wide isotopic ranges. In contrast, specialists such as orangutans, tapirs, and rhinoceroses showed narrower profiles tied to particular habitats. As environments shifted, generalists endured while specialists were left vulnerable.

Orangutans, now limited to Borneo and Sumatra, once ranged widely across Southeast Asia. Isotope results suggest they consistently relied on fruit from closed-canopy forests, even during environmental change.

“Even though modern orangutans can turn to alternative foods during hard times, their survival still depends on intact forests,” says Dr. Nguyen Thi Mai Huong, co-author from the Anthropological and Palaeoenvironmental Department of Vietnam’s Institute of Archaeology. “It looks like this has been true for tens of thousands of years.”

With Southeast Asia facing the fastest tropical deforestation worldwide, the lessons from the past are urgent. “Understanding how species coped with ancient pressures helps predict their resilience today,” said senior author Prof. Patrick Roberts of the Max Planck Institute. The study highlights the need to conserve not just species, but the ecological conditions that sustain them.

“This is about more than just ancient animals,” Bourgon adds. “It’s about learning from the past to protect the future.”